by Marquaysa Battle

Nat Turner, a slave and preacher prone to visions, masterminded one of the most violent and impactful slave rebellions in American history. On the evening of August 21, 1831 in Southampton County, Virginia, Turner led over 70 slaves from plantation to plantation, killing every slave owning white family, including women and children. The point was to grow an army full of slaves and make it to nearby Courtland (then called “Jerusalem”) to further arm themselves and overthrow the slavery regime in Virginia, if not the entire South.

I visited Southampton County to trace Turner’s steps. Given Turner's impact on American history, I expected to find some of the houses from the rebellion still erect, and marked as historic sites. At the bare minimum, I was hoping to visit a display of artifacts from the rebellion in a nearby museum or see an official grave.

The Southampton County Historical Society has Nat Turner’s sword and other artifacts from the time period, but have yet to put them on display. The local courthouse periodically displays documents about Turner, including a FOX script for a 1970s Turner film that never happened. But they’ve been put away. Nearly everything about the preservation of Nat Turner’s legacy by Southampton County is out of sight, gone or ‘in process’.

There's not even an official burial place or memorial site for Nat Turner. In fact, his whole body is not in the state of Virginia. Turner was decapitated by hanging and his skull has changed several hands over the years. According to the Baltimore Sun and Rick Francis, the current Southampton County Clerk of Circuit Court, the last known whereabouts of Turner’s skull are somewhere in Indiana, where it was once in the possession of the National Civil Rights Hall of Fame. The newspaper also shared that his torso was buried in a pauper’s grave in Courtland, which was later destroyed by road construction.

And um, his skin? Francis maintains that “floating around here somewhere is a purse of the hide of Nat Turner.” Big freaking gulp. Words cannot even explain what my heart did when Francis casually mentions that the skin of a slave was turned into an accessory.

Francis is still working to get the purse, but no luck thus far. According to him, a Courtland resident is “jealously guarding it”, afraid that he will take legal action to acquire it for the city. When asked what he would do with the Nat Turner skin purse, he replied, “I don’t know. I haven’t thought that far.” What he has thought about is Nat Turner’s skull. “We would enter it into a properly marked grave," he said. "The skull should be buried after being fully studied.”

I thought I might have better luck learning about Turner on the Nat Turner Trail, hosted by H. Khalif Khalifa, the founder and owner of the Nat Turner Library and Nat Turner Trail tours. Khalifa has spent more than 20 years of his life trying to preserve Turner’s legacy.

H. Khalif Khalifa, in the Africa Room of the Nat Turner Library

The Alabama-born elder and long-time Southampton County resident purchased 123 acres of Nat Turner’s old stomping grounds. He's written two books about Nat Turner, curates a black liberation library in his honor and conducts a trail that traces Nat Turner’s steps from the place where Turner allegedly had his first vision of a rebellion to the approximate location where he was captured, tried and hanged.

According to Khalifa, Nate Parker, who produced, directed, and stars in the upcoming Nat Turner biopic, The Birth of A Nation, stopped by to pick his brain about Turner. "Oh yeah. Nate Parker, he’s been here," Khalifah recalls. "He set his lights up. He interviewed me for an hour or so."

Khalifa described Parker as, “well-prepared, well-qualified. Master of his craft. Knows he wants to use the skills and the profession he’s in to make a contribution to the liberation of African people.”

Our first stop on the tour was the plantation, now a green field, where Nat Turner was born. There, Khalifa shared stories about Nat Turner’s childhood—specifically his reputation for being highly intelligent and making ink and gun powder at an early age. Khalifa also spoke of impactful events in Turner’s life, including the death of his master, Benjamin Turner. After his first master's death, Turner was sold twice, eventually working under an overseer who beat him severely.

We visited that plantation, also a field, next. Khalifa explained that harsh treatment by the overseer caused Turner to eventually go into hiding, where he allegedly had his first vision of a rebellion. Turner returned to the plantation and began to organize his army. This is also the site where Turner began his rebellion. He kicked off the insurrection by killing his current slave master first.

As the tour continued, we passed other plantation sites, mostly empty fields, that Turner’s army attacked. One of the most interesting locations was where Turner’s wife, Cherry, lived. Cherry’s slave owner and his family were killed the night of the insurrection. Khalifa also shared that rumors spread about Cherry betraying her husband and turning him into the white militia. They were never proven. Cherry’s cabin was demolished a few years ago.

“Some visitors on a tour I did a few years ago wanted to take a few pieces of the cabin with them,” Khalifa recalled. “Had I known they were gonna tear it down, I would have just let them take what they wanted.”

Unfortunately, there weren’t many historical homes to see on the tour. The home of the Porter family, who escaped Turner’s attack because a slave named Alston escaped the first plantation and warned that Turner and his army were en route, is still standing, but looks as if it will collapse any minute.

The Porter house

There’s also the Rebecca Vaughan house, one of the last sites targeted during the Insurrection. The house, “donated” to the Francis family and a few other Southampton County residents who are working to create a museum and official Southampton County tour, is not in its original location.

The Francis family was among the many killed during the rebellion. So yes, a family whose slave owning ancestors were killed during Nat Turner’s insurrection now have a hand in the preservation of Nat Turner’s legacy. Francis, one of the family's descendants, says the planned tour will not be specifically for Nat Turner, but will instead cover the “entire era”.

The Southampton Courthouse and jail where Nat Turner was tried and hanged stands in the same location, but it has been rebuilt.

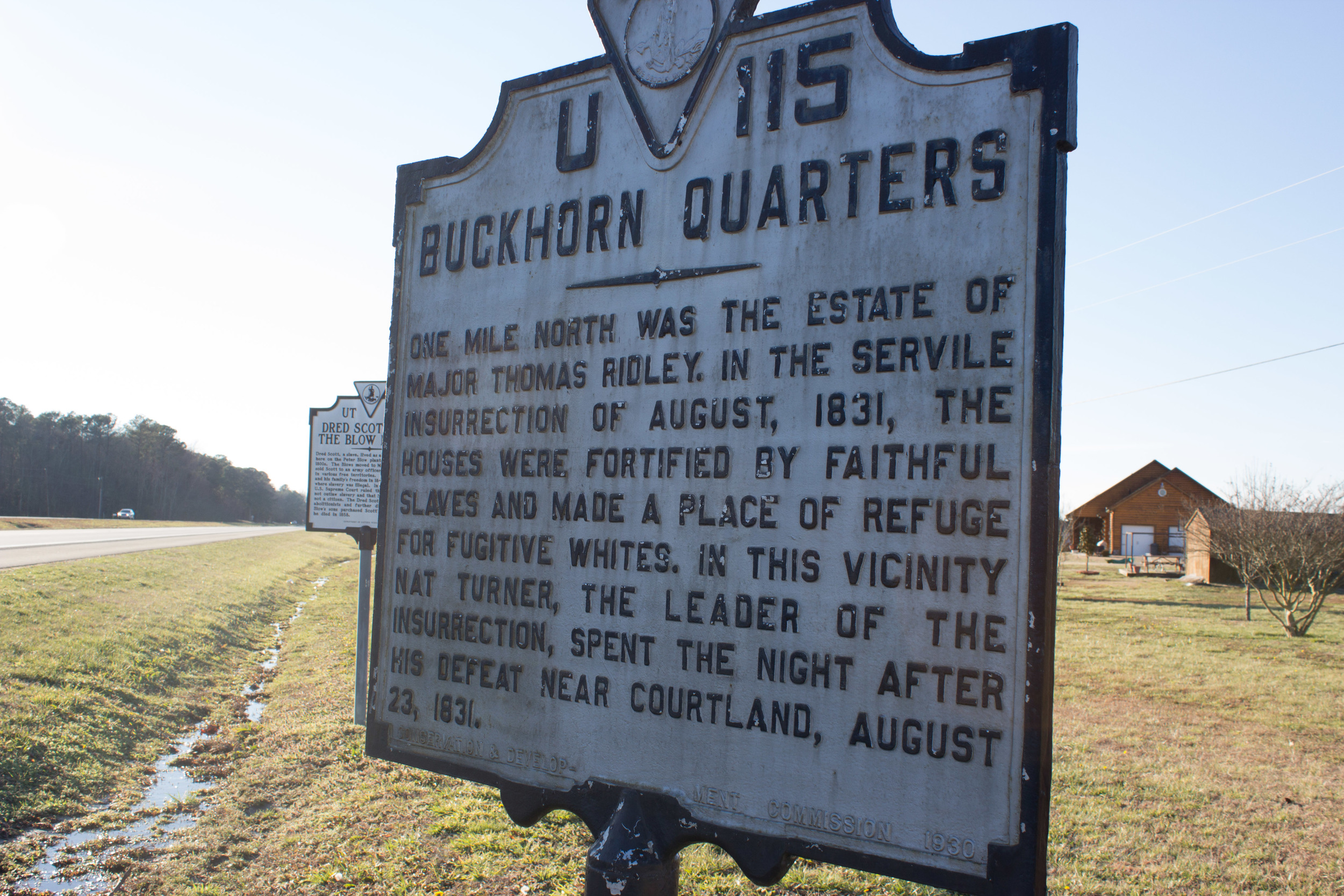

More or less, Turner's rebellion is only acknowledged by two signs. Near an empty field, there's a roadside signpost with an overview of the Insurrection.

The other sign marks the estate of Thomas Ridley, which avoided being attacked because slaves protected it. The estate became a "place of refuge" for white families fleeing Turner's attack. Turner spent the night "in the vicinity" after the rebellion was quelled.

That sign sits near another sign acknowledging Dred Scott, a slave who was also from Southampton County. He attempted to sue for the freedom of himself and his family after living for years with his master in a free state. In an infamous Supreme Court decision, the court ruled, black people were "so inferior that they have no rights which the white man is bound to respect." The two signs stand there, intentional or not, representing black resistance during slavery.

I asked Khalifah what he wants people to get out of his tour. Khalifa said, “I want them to take away the fact that somebody fought for our freedom in an uncompromised way. Nat Turner did not compromise when he made the decision to take the route he did. Nat Turner did what he did so we could do what we do today.” Khalifa acknowledged that the tour was much fuller and more impactful before Southampton County demolished most of the relevant homes.

At the end of the tour, my mind was blown. I left thinking about how underrepresented the once enslaved men and women of Southampton County are. With the shaky circumstances surrounding Nat Turner artifacts and even his body, folks who are interested in Turner's story need The Birth of a Nation film like yesterday. It will be a long time, if ever, before the story fully tumbles out in Southampton County.